Yankee in the Garden 32.078098° -81.082878°

25m | Mar 13, 2023Hey, everyone!

Did you hear that?

Somebody said, “The Yankees are coming!”

Actually, we hear that all the time here in Savannah, Georgia.

Today it would mean they were coming down for a few days of vacation… But back in 1864, it didn’t mean they were stopping in town to catch dinner at Sweet Potatoes Kitchen and buy a couple of tee shirts down on River Street.

It would have been a little more distressing when those words were spoken around South Georgia.

And so… to go with that… here’s a great story about a Union Prisoner of war in Savannah at the end of the American Civil War who heard those words and was very relieved…

His story… gives you a perspective that you don’t often hear.

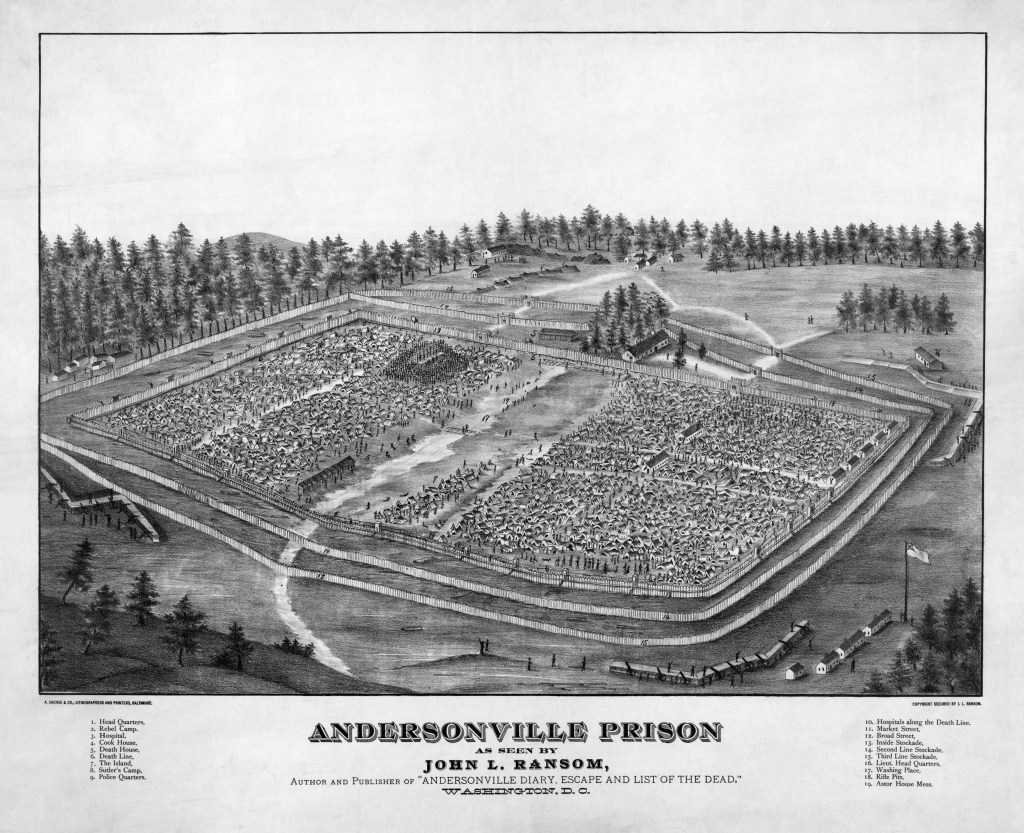

Because in 1864, Union soldier Frederick Emil Schmitt and others endured the stench of filth and death in the infamous Confederate Civil War Prison camp near Andersonville, Georgia.

Andersonville_Prison by John L Ransom former prisoner.

Andersonville_Prison by John L Ransom former prisoner.

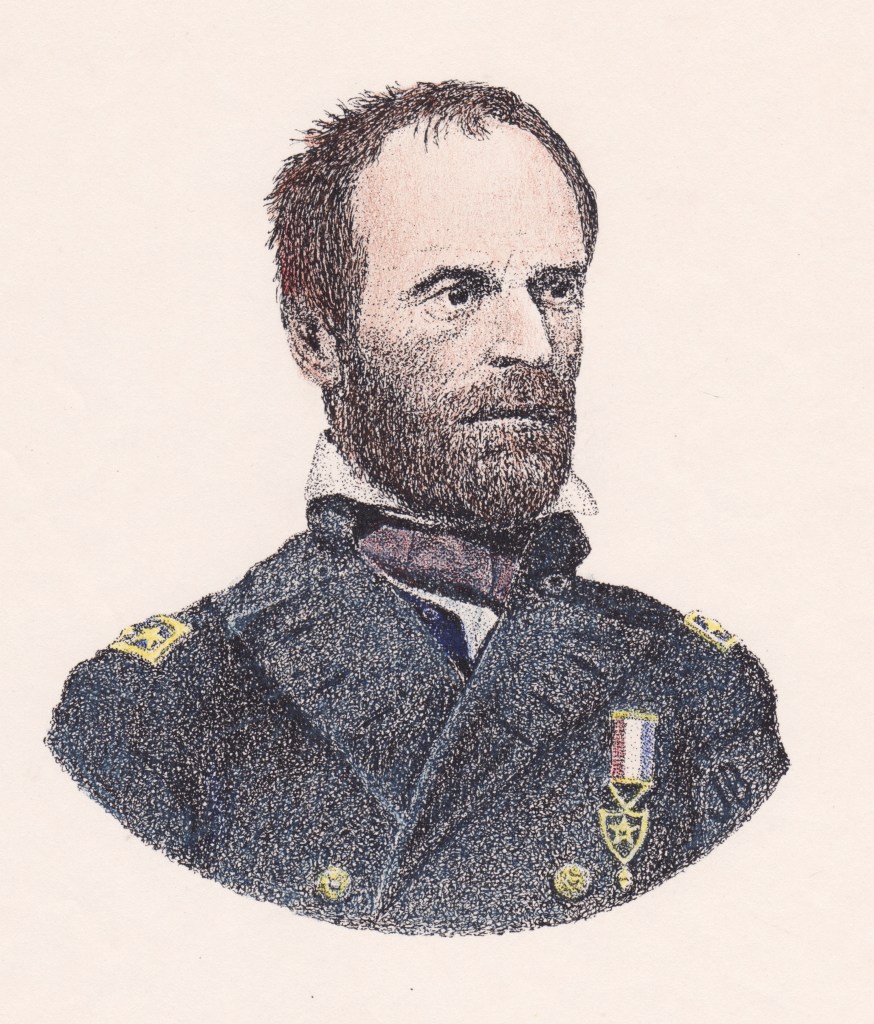

But out of a stroke of genius and luck, he ended up in Savannah, hiding from the Rebels and waiting for the arrival of the army of Union General William Tecumseh Sherman.

Union Major General, William T. Sherman.

Union Major General, William T. Sherman.

He has a great story that almost fell into obscurity. Sick around and I’ll give you my take on it.

I'm JD Byous. Welcome to History by GPS, where you travel through history and culture, GPS location by GPS location. So click on your favorite map app and follow along.

The coordinates for the location talked about in the podcast

32.078098° -81.082878°

Now… on to our story… which, by the way… is one of three interesting historical events that happened years apart at this same location… we’re talking physically on the same spot of ground within a ten-yard circle.

You’ll find those stories noted at the website too.

For this episode the spot plays an important role in the life of Frederick Schmitt because he ended up hiding within this small tiny circle on the globe.

If you recall the story of Andersonville, almost 13,000 of 43,000 Union prisoners died from hunger and disease during the years the prison was operating… 1861 to 1865...

Now… I might add that similar conditions were experienced in Northern prisoner-of-war camps. There were no picnic either… but you don’t hear as much about them.

The South lost the war in case you haven't heard

And… as is always espoused… The victor writes the history.

What made things worse in the South was that the population was low on food and provisions, which made prison life a living hell.

By the way, JD Huitt over at The History Underground on YouTube has a great episode about the conditions at Andersonville. I’ll put the link in the show notes. It’s well worth a look.

Okay… There at Andersonville… One day Frederick Schmitt’s luck changed in October 1864 when he noticed a group of prisoners by the main gate being placed in rank and file as if they were getting ready to march outside. It was drizzling rain when he saw his chance for a difference in scenery.

But who was Frederick Schmitt?

Great question! I’m glad you asked. It fits right in with the next part of the story.

Schmitt came to America from Bavaria in 1859, settled in Elizabeth, New Jersey, and enlisted in the Union Army on February 10, 1864. He held the rank of private in Company D, of the 3rd New Jersey Cavalry regiment under Colonel Andrew J. Morrison.

By June 1864, he was in the Union Calvary under Major-General James H. Wilson and found himself captured after the rebels raided his position outside of Richmond, Virginia. His friends and officers couldn’t find him and thought he was dead and they listed him as being killed in action.

So, most of his military life… military experience… was in Prison.

In 1919 he wrote his memoir of being a POW when he was 77 years old, fifty-five years after his experience in the South.

But… ironically… his story wasn’t published until 1958, when his daughter gave it to the Wisconsin Historical Society.

So, I guess there’s hope for some of the articles I wrote back in my newspaper days…

Not much is known about Schmitt. I do know that he was an engineer, and I did find a master’s thesis written at the University of Wisconsin in 1904 by a Frederick Schmitt.

It was on mass transit, you know, street trolleys, and things like that, and as far as I can tell, he was in that field… being an engineer, so he could have written it, I suppose.

However, I suspect it may have been a son or someone else since he… Frederick… would have been 62 years old by that time.

Then again… I got my history degree at the ripe old age of 53, so who knows.

His recollection of the prison is an intriguing story in that it… bends, the typical narrative about Andersonville with an interesting perspective. It tells of his kindness toward his captors in a way that other prisoners did not record nor recollect afterward. At least as far as I’ve seen.

Schmitt said… and I quote…, “Personally, I witnessed no cruelties to individuals, except such as resulted from general conditions.”

He goes on, “The Southern States in 1864, being themselves short of foodstuffs, could give prisoners only such food as they themselves had… and the Rebel soldiers about the camp had no better food than the prisoners.”

Quite magnanimous, I would say.

Interesting, indeed.

So, on one cold morning, Schmitt’s odyssey to freedom began after a night of discomfort made him get up and start moving around… work the kinks out after sleeping on the ground.

He wrote, “Being stiff and cold I got up, slung my haversack over my shoulders, and began to walk down toward the driveway where I hoped to get a chance to warm myself near one of the bake ovens.”

If you’ve ever seen a map or drawing of the prison, there were a couple of ovens in the bakery that were fairly large… a good place to get warm.

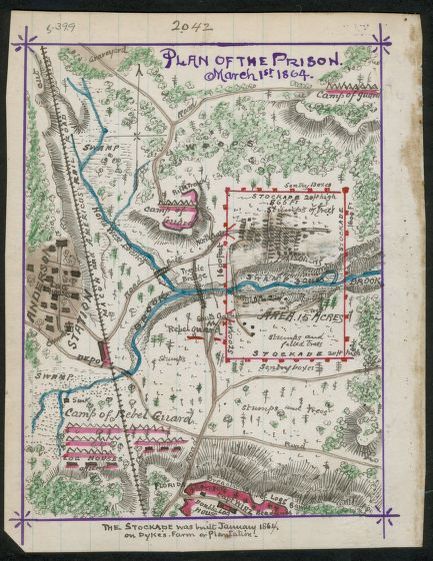

Well, the sound of drums beating caught his attention. Over near the gate, a detachment was ordered to fall in to be taken to the train.

He said the column was already marching, and the first row was already outside of the large stockade gates. Schmitt slipped into the lines but was seen by one man in the line who recognized him as not one of the chosen group.

He immediately pounced upon him and tried to push him out of the marching column but only succeeded in pushing him back to the next row. Then Schmitt was jostled further back in the line, where he finally ended up in a group of men who didn’t care… or… thought he was one of those selected.

As they marched out of the compound, two Rebel officers stood on each side, counting the men who passed.

Schmitt’s line was in the last row to be allowed out of the gate. Just as his line was counted, the men behind him were stopped. Schmitt did not know where he was going, but anywhere was better than Andersonville.

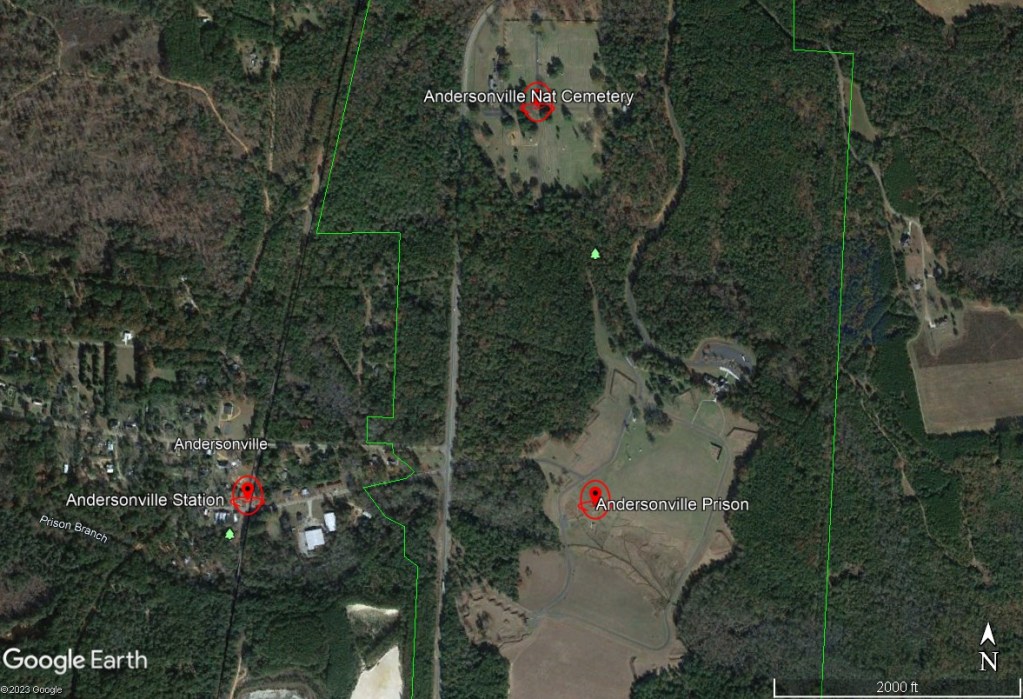

Andersonville Prison 32.194906° -84.130172°

Andersonville Station 32.194878° -84.139204°

A Google Earth view of Andersonville, Georgia, the prison site and the National Cemetery.

A Google Earth view of Andersonville, Georgia, the prison site and the National Cemetery.

Union prisoner and artist, Robert Knox Sneden's map of Andersonville, the train station and the prison site. Library of Congress.

Union prisoner and artist, Robert Knox Sneden's map of Andersonville, the train station and the prison site. Library of Congress.

By the way… Remember that the show notes and GPS locations for all of the spots mentioned in this episode can be found in the show notes or at History By GPS dot com. While you’re there check out our books and merchandise. I think you’ll like our line of products from Savannah and its history… including some that highlight this episode.

And leave a comment. I’d love to hear your opinion or information that other listeners would like to hear.

Meanwwhile… Back at Andersonville Station… Schmitt and the other men were loaded into railroad boxcars and told their destination was the Savannah POW camp that covered the 700 block along Whitaker between West Hall and West Gwinnett Streets across from Forsyth Park.

I’ve looked in my notes but can’t find the name of that prison.

I think it may have been Camp Mercer or Camp McLaws, but my notes… and my memory… have slipped away somewhere.

However, if you know the name of the Savannah camp, please let me know in the comments or on the website, HistoryByGPS.com.

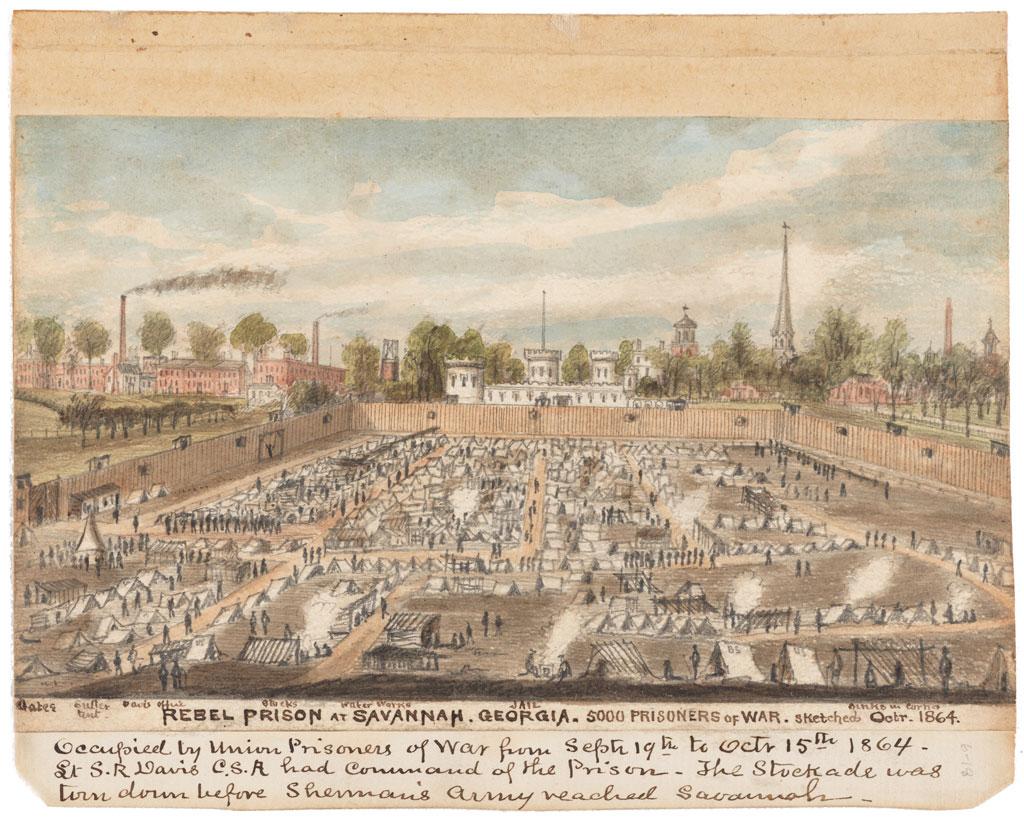

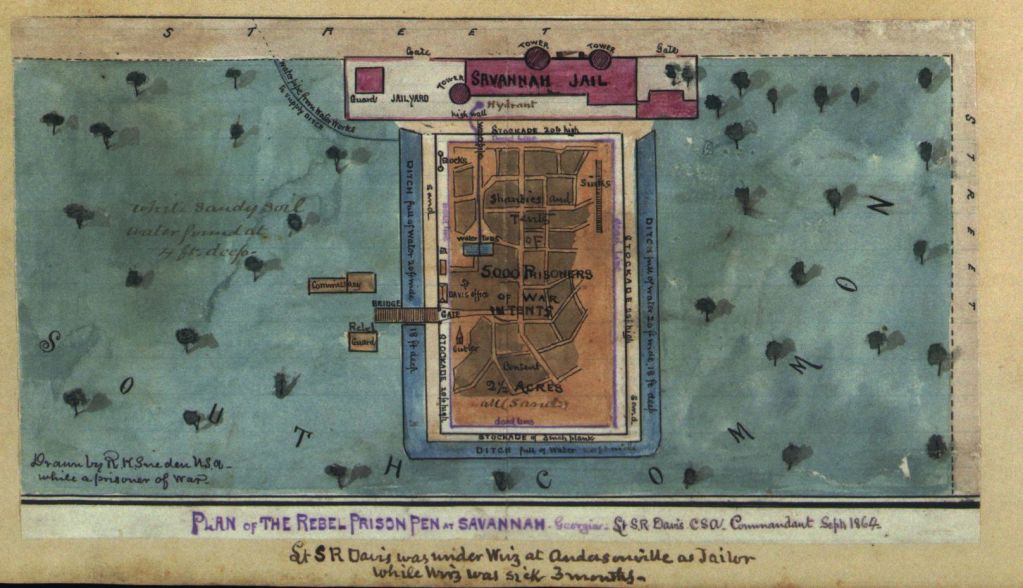

Now, by chance, POW artist Robert Knox Sneden was in the Andersonville and Savannah prisons with Schmitt and was in that same group of men who were transferred to Savannah. Sneden captured the compound on paper and ink, and many other war-time details that were… and still are… available in books. I’ll have a couple of his drawings I found in the Library of Congress archives in the show notes.

Savannah POW Prison 32.068114° -81.097359°

Savannah's Historic District with POW camp and Trustees' Garden.

Savannah's Historic District with POW camp and Trustees' Garden.

Now, Schmitt… after a few weeks in the new prison yard that he describes as “utter misery,” …another stroke of luck came his way. One morning a commission led by a Union officer, a Captain named Gottheil came to the gate to recruit men to work in a local machine shop.

The Prison camp at Savannah, Georgia by Robert Knox Sneden, 1864.

The Prison camp at Savannah, Georgia by Robert Knox Sneden, 1864.

Hearing that Gottheil was looking for workers who were machinists, again, Schmitt’s grit placed him in an advantageous position, so he made a rapid jump toward the gate. But as soon as he made a step or two, one of the self-appointed guards saw him and ran at him, ready to strike.

See, a set of POW rowdies had taken over the internal government of the camp. Each of them carried a huge hickory stick, Buford Pusser style if you are old enough to remember that story…

The ruffians only let men who had paid them approach the gate.

But when Schmitt ran for the gate, Captain Gottheil warned the henchman off and let Schmitt approach and talk to him. So, he was able to tell him about his engineering experience.

He was chosen… so he and a small group of POWs were marched across town to Alvin Miller’s Iron Foundry on the on the bank of the Savannah River, about 300 yards east of Trustees’ Garden and the Savannah gas works.

It was located on the spot where, today, the Thompson Hotel stands.

Alvin Miller’s Foundry 32° 4’38.67 “N 81° 4’43.97 “W

Trustees' Garden and the gas works are show on upper right with smoke from Miller's foundry site shown at the lower (extreme) left side of this 1871 birdseye view of Savannah.

Trustees' Garden and the gas works are show on upper right with smoke from Miller's foundry site shown at the lower (extreme) left side of this 1871 birdseye view of Savannah.

There, Schmitt and his fellow prisoners were turned over to the manager of the foundry and told to wait. Later, Schmitt was shown a small horizontal stationary engine and asked to overhaul it so it could be installed in a boat.

I talk about Alvin Miller’s foundry in another episode about survivors of the Charge of the Light Brigade… So, that's another story.

With Schmitt’s new job came a near unlimited freedom to roam around the city. Often, on his off time, he often visited the gas works, where he met the superintendent, James Smedberg, as Schmitt described, a Scandinavian and a Union sympathizer.

If you may noticed, Schmitt’s recollection has almost everyone he met as being a Union sympathizer… then again… who knows… I was out of town that day.

But then, again, when folks found out that General Sherman was on his way to town… I can imagine that many people were choosing a different side of the political conflict.

Now, Smedberg… The superintendent… he pops up in another episode about the Confederacy’s Silk Dress Balloon… so stay tuned.

When Smedberg wasn’t around, Schmitt sneaked into the retort house and got to know the stokers, many of whom were black locals and Irish immigrants.

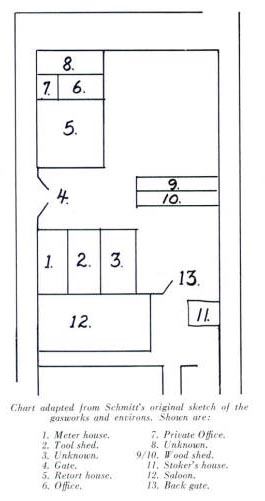

The Gasworks buildings, now the Charles H. Morris Center, with locations of the coal (wood) shed, the worker's hut, and the meter house sites.

The Gasworks buildings, now the Charles H. Morris Center, with locations of the coal (wood) shed, the worker's hut, and the meter house sites.

Now, to explain, a retort… is an oven where coal was cooked to make gas for streetlights, stoves, and other industrial and residential uses. It was similar to the natural gas that we use today.

The retort operation was a hot and dirty job where coal was heated over coke fires… not Coca-Cola, coke, the charcoal-like stuff, except it burns much hotter.

The gases from the hot coal were refined into residential gas but also into benzyne, ammonia, acetate, and other by-products. Now, don’t ask me how… It’s a bit like magic or alchemy to me… I definitely wasn’t a chemistry major in school.

Well, with the swirl of rumors saying General Sherman was marching to the sea at Savannah… according to Schmitt… many workers were eagerly awaiting his arrival.

So… many befriended the near-celebrity POW.

Over at Miller’s foundry, the man he worked under was a German named “Mr. Weber,” who took Schmitt to his home and introduced him to his wife and children as well as other German inhabitants of who, mostly, were Jews. According to Schmitt, it seems that all of Savannah eagerly awaited Sherman’s arrival…….

Now… I tend to have reservations about his conclusion.

But, do you know what I don’t have reservations about.. it’s that you should go to our website at HistoryByGPS.com and check out our merchandise. Just thought I’d throw that in again in case you’re at work and the boss was talking to you the first time...

So… In anticipation of Sherman’s army, restrictions on the POW became even more relaxed. It was then that a prison friend joined Schmitt, a guy he called, a little German Jew named Loewenstein. The small-statured man became his constant companion on his trips to the gasworks and around town. So, Lowenstein, too, became friends with the gasworks workers.

I should mention that there is and was a substantial population of Jewish folks in Savannah. And that Schmitt mentions going to dinner at their homes in his story.

It’s highly believable since Savannah has our country’s third oldest congregation here. And the community is known for its Southern hospitality.

Around that time, Captain Gottheil … the officer that recruited Schmitt at the prison… Well, he walked up to Schmitt and told him that the Union Army was only two days away, so he… Gottheil … and the others in charge of the prisoners getting the heck out of town. And, as far as he was concerned, Schmitt and Loewenstein were on their own.

Now, remember, the Confederate Army was still in Savannah. A few days later, they built a pontoon bridge across the river and escaped into South Carolina.

If the two prisoners were found by the rebels, they would be taken into custody and marched away from General Sherman and freedom.

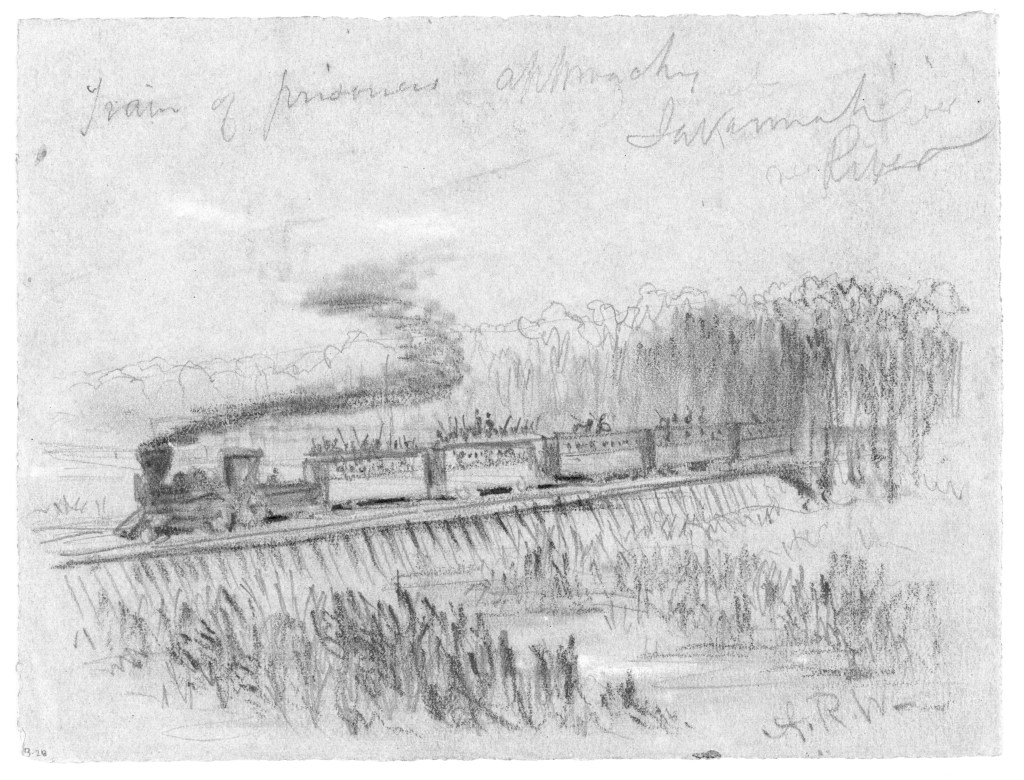

In fact, weeks earlier, before they suspected that Sherman’s Army was coming to Savannah, the POW camp prisoners across town, including artist Robert Knox Sneden, were shipped to another location… they went to the newly built Camp Lawton near Millen, Georgia.

The Union prisoners at Camp Lawton near Millen, Georgia were loaded into boxcars when General William T. Sherman's cavalry came near, by Alfred R. Waud, Library of Congress.

The Union prisoners at Camp Lawton near Millen, Georgia were loaded into boxcars when General William T. Sherman's cavalry came near, by Alfred R. Waud, Library of Congress.

Ironically, it was directly in the path of the Union army. When Sherman’s cavalry approached, the prisoners were put back on a train and shipped out again. Some went to South Carolina, and others to Blackshear, Georgia, southwest of Savannah.

As a side note… I’ve heard Lawton Prison called the world’s largest… I guess, prisoner of war enclosure… I really have no idea if that’s true. If you happen to know let me know in the notes.

So, with things getting hot in town, one evening, Schmitt and Loewenstein slipped out of their quarters at the foundry, walked to the gas works, and contacted the workers. Some of the employees took them and hid them in the meter house that was located at the back of the Pirates’ House building.

The next day Superintendent Smedberg discovered the stowaways and was livid with the stokers, scolding them and demanding that the POWs leave.

Another little side note here… A few years ago, I walked past that spot where the old meter house would have stood. Plumbers were laying pipe for the extension on the Pirates’ House restaurant and were working inside an old brick foundation about the same size as the meter house was described. I’ll put that location in the notes.

Meter House 32.078244° -81.083667°

Now, Smedberg had a good reason for being angry. If the rebels found the prisoners in their hiding spot, he and the gas works men could have been shot for aiding the enemy.

Schmitt and Lowenstein begged to be allowed to stay in hiding until dark but the Superintendent would not listen, so there was nothing left for them to do but leave.

However, one of the workers whispered to the two that he would leave the back gate unlocked. So later that night, the two men returned.

The back gate was next to the bluff where Wright and Reynolds Streets met. Today, the fence of Morris Park and the Morris Center terrace meet on the northeast end of the parking lot.

The POWs were ushered into a large coal shed that, at that time, held split-pine firewood and crawled to the top of the pile.

Now that's where today's GPS location will take you. It was on top of that spot where our story intersects with other episodes within a fifteen foot radius or so.

Location of three stories, Magazine, Balloon, and Prisoners

32.078103° -81.082939°

Schmitt noted that their bed on split logs had few smooth surfaces and was in reality a bed full of splinters and sap.

He wrote that the resting place was the worst one he’d ever found… and that, to quote, “Smedberg’s findings for the perfect size pieces was great for making gas, but poor for hours of sitting and sleeping.”

After dark, a stoker who lived a few yards away came to their hiding place, whistled to the men, and told them that supper had arrived. They were given cornbread and they ate it on top of the rough cordwood.

The next evening another whistle was heard… but that time they were invited to join the stoker at his home. A crude map drawn by Schmitt indicates that it stood next to the spot where, today, the two fences meet, next to the brick wall and the parking lot. I’ll put Schmitt’s map in the notes as well.

Well, the two Yankee POWs were invited to stay and eat dinner. After a day and a night on their pinewood bed, the invitation was welcomed without any hesitancy, as Schmitt said, “for we had by this time not a painless spot in our bodies, and the expectation of getting a seat on a chair overcame every scruple.”

Worker’s hut (#11 on map) 32.078045° -81.083195°

He described the home as being typical of shanties in Trustees’ Garden and that the tiny house was, to quote, “no better than an Irish or Negro house” and was sparsely furnished. The room was illuminated by pitch-pine sticks that filled the area with a cloud of soot.

Those pitch-pine sticks, to those of you from the South, were what we call fat Lighter… great sap-filled kindling wood.

The Schmitt was thankful for the hospitality but said communication was difficult. He explained… “The good people gave us food and entertained us, although we hardly understood their jargon.”

They were probably speaking Gullah or English with a Gullah bent. It’s the language of many of the families who had been brought over as slaves from the Sierra Leon region in Africa.

As the visitors talked, rumbling noises came from the commercial section of the city. The last of the Rebel forces were destroying property to prevent it from getting into the hands of the Union soldiers.

Unfortunately, in the chaos, others looted empty buildings as the Rebel army gathered on the river to exit across the pontoon bridge near the foot of West Broad Street. That road is now renamed Martin Luther King, Junior Boulevard.

After the evening was spent, the two soldiers returned to the woodpile and spent another sleepless night.

Schmitt described that the Rebel soldiers ruined the food supplies of the homes, making them inedible so the Union forces could not use them. Some days afterward, he said he saw some of this work which he described as a savage and gruesome aspect. Rice, molasses, kerosene oil, vegetables, and dry goods were all in a heap on the floor to the depth of a foot or two, and of course, everything was spoiled.

He didn’t know that Sherman’s men did the same thing to homes along the route from Atlanta as it swarmed the Georgia landscape as he marched to Savannah. Many families in Georgia, including my wife’s, tell how Sherman’s Bummers destroyed their food supplies similarly and left them in their homes with nothing to eat.

General Sherman's army in a victory parade along Bay street in front of the Exchange Building at the intersection of Bull Street. Library of Congress.

General Sherman's army in a victory parade along Bay street in front of the Exchange Building at the intersection of Bull Street. Library of Congress.

Well, the next morning, a call came from below the woodpile telling them “the Yanks are here.” The two men quickly crawled down and made their way to the main gate.

Main Gate to Gas Works 32.078406° -81.084128°

Schmitt said… In less time than ever before, they were on the ground and out of the iron gate on East Broad Street. There they found the street full of Union soldiers. But being clad in surplus Rebel uniforms, they became objects of suspicion, so there was nothing to do but surrender and be asked to be taken to the provost marshal’s office.

In their interrogation, they explained their status, they received an identification mark, an order for a day’s rations, and orders to report back every morning.

On of the first things they did was to repay the kindness of the Savannah residents who had welcomed them into their homes. They took their rations to the families and invited their hosts to share the food and eat with them, which they repeated every day for about a week or ten days.

Then one day the men were given orders and required to leave quickly by way of an ocean steamer that was bound for New York.

They never saw their unfortunate-found friends in Savannah again.[1]

According to the Wisconsin Magazine of History, when Frederick Schmitt died, he requested to be cremated. Then to be buried under a rose bush in his daughter’s backyard… at 821 Cherry Street in Green Bay, Wisconsin.

So if you’re in the neighborhood, leave a flower on the sidewalk out in front of his resting place and remember an old veteran… who was as much a veteran of a prison camp than a veteran of battle.

Schmitt’s daughter’s home 44.512042° -88.006193°

So…. if you didn’t already know this story… now you know.

Please remember to click the button and follow, then go to our website HistoryByGPS.com to find more info on this episode. And others

See you next time

Bye

-------------------------------------

The History Underground, JD Huitt, https://www.youtube.com/@TheHistoryUnderground

GPS Coordinates:

Woodpile and stories on same spot, 32.078103° -81.082939°

Andersonville Prison 32.194906° -84.130172°

Andersonville Station 32.194878° -84.139204°

Savannah POW Prison 32.068114° -81.097359°

Alvin Miller’s Foundry 32° 4’38.67 “N 81° 4’43.97 “W

Meter House 32.078244° -81.083667°

Worker (Stoker) hut 32.078045° -81.083195°

Schmitt’s daughter’s home 44.512042° -88.006193°

Bibliography

[1] Prisoner of War: Experiences in Southern Prisons by Frederick Emil Schmitt, Wisconsin Magazine of History, pp 83 – 84, 1958: Andersonville National Historic Site, https://www.nps.gov/ande/learn/historyculture/camp_sumter_history.htm.

© History By GPS, JD Byous, all rights reserved, 2023